Breaking the Silence: Gender-Based Challenges in the Lesotho Highlands Water Project ll

MASERU, Lesotho, Apr 3 2024 (IPS) – In the journey towards gender equality and justice, recent decades have seen strides made, yet the road ahead remains treacherous. In the race to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, attention is turning to the role that over five hundred public development banks worldwide could play.

Public development banks are increasingly exploring how to promote financial inclusion more effectively, as an important vehicle for women’s economic empowerment. Financial inclusion transcends mere access to capital; it is a radical shift of social norms, addressing social issues that hinder women’s advancement.

However, in many projects funded by PDBs, women are not only excluded and left behind, but are put in a position of harm. One such case is the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) where there is growing evidence of a wide range of negative gender impacts within the affected communities.

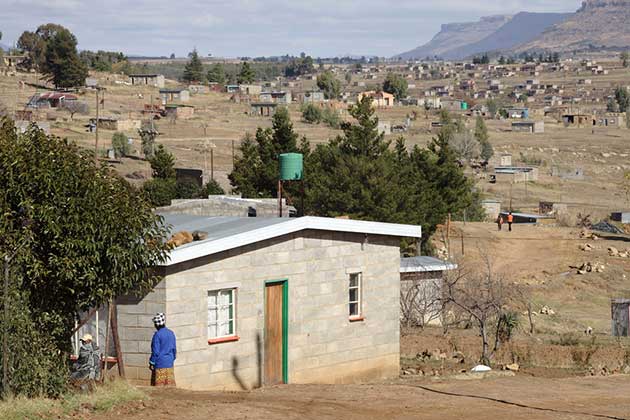

The objective of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is to provide water to the Gauteng region of South Africa and to generate hydroelectricity for Lesotho by harnessing the waters of the Senqu/Orange River in the Lesotho highlands through the construction of a series of dams.

Hailed as a remarkable engineering feat with anticipated economic benefits, it has instead garnered international notoriety for its severe socioeconomic and environmental repercussions on communities. Phase I of the project led to the displacement of thousands without fair compensation, submerging arable and grazing land, exacerbating erosion, creating impoverishment, “social disintegration”, and limiting access to water resources.

Despite long-standing concerns and documented impacts on communities, including increased HIV/AIDS risk, the project proceeds with Phase II without adequately addressing residual issues.

The project’s impacts disproportionately affect women, exacerbating vulnerabilities through increased risks of displacement, lack of access to water and healthcare, and heightened instances of sexual exploitation, contributing to a cycle of socio-economic marginalization and health disparities.

Gender inequality in Lesotho remains a problem despite progressive legal strides in recent years. Implementation and enforcement of laws, especially in rural communities, continues to be a problem. Outdated cultural practices and stereotypes continue to create barriers to ownership of land, denying women the resources needed to secure livelihoods and increasing their economic vulnerability and susceptibility to gender-based violence.

Seinoli Legal Centre (Seinoli) is a Lesotho based public interest law centre that has been working directly with the affected communities in the Mokhotlong district where LHWP Phase II is being implemented, since the signing of the Agreement on Phase II in 2011.

Increased incidents of gender-based violations have been reported within the project affected communities which should come as no surprise; projects of this nature and scale, including the resultant forced displacement often amplify the risks of gender-based violence.

Furthermore, there are thousands of migrant workers from Lesotho itself and South Africa, who have come to work on LHWP. Migrant workers should be accommodated in designated camps, in healthy accommodations and living conditions in accordance with best practices. The situation on the ground stands in complete contrast to this; there are contractors living and renting accommodation within the communities of Masakong, Ha Ramonakalali, and Tloha-re-Bue. In the case of Ha Ramonakalali, there is also a temporary camp belonging to one of the private companies contracted to work on LHWP which is located within the communities – having profound impacts.

Cases of transactional sex between migrant workers and young women and girls have increased, including cases of abortion and concealment of birth, human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and high school drop-outs.

Seinoli was recently alerted to the predicament of the fifteen-year-old Lineo (name changed to protect the victim and her family) and her parents. This young girl was impregnated by one of the migrant laborers working for an LHWP contractor. Lineo decided to have an illegal abortion – as abortion is prohibited in the country -in fear of her parents. The abortion led to health complications, which necessitated informing her parents about the events. Lineo’s parents made a complaint to the police. Seinoli received a report that the police were not able to make charges against the perpetrator as they could not locate him after he was moved to another camp by his employers. Consequently, the young girl has been left with the scourge and stigma of having had an abortion and lives in shame within her community. She has also been forced to drop out of school, which will have severe repercussions on her future and ability to earn an income.

The LHWP receives substantial funds from PDBs such as the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA), the New Development Bank (NDB) and the African Development Bank (AfDB). While these banks do indicate concern for gender equality, more needs to be done for the development and strengthening of their gender strategies to ensure that the projects they fund do not violate women’s safety or security.

Currently, the Lesotho Highlands Development (LHDA), the project’s implementing authority, does not have a safeguarding policy to protect communities against sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment risk to ensure accountability.

Communities need to be better informed about their rights and have access to reporting mechanisms which can lead to expedited support for victims whilst holding the perpetrator and their employers accountable.

It has been five years since LHWP Phase II commenced, with advanced infrastructure works since January 2019. However, there has not been any shift towards protecting the rights of vulnerable women and girls since the project begun.

The role of international financial institutions and PDBs in fostering gender equality has been discussed extensively in many quarters, including the academic and research communities. However, many questions remain on the commitment of PDBs to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment.

In practice, concerning some of the public financiers of the LHWP, the NDB still does not have a gender strategy or policy in place despite having been fully operational for close to 10 years. The DBSA and the AfDB represent financiers of the LHWP with a gender policy or strategy, however, the effectiveness of their gender frameworks is questionable considering the challenges that women are now being exposed to in projects such as the LHWP Phase II.

Basotho women faced similar difficulties during the first phase of the LHWP when women, including female-headed households were excluded from families who received some limited minimal compensation for resettlement. Women were extremely vulnerable to gender-based violence, not only physical but also economic violence. During that time, the World Bank was a major financier involved in the construction of the Katse Dam.

The World Bank gender framework has evolved, providing finance to the LHWP Phase I. The World Bank has now integrated safeguard policies against sexual exploitation and abuse in its Environmental and Social Framework as well as Procurement Framework.

These frameworks ensure that development projects take measures to reduce the risk of sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment, especially within communities. After civil society groups raised complaints about gender-based violence associated with a World Bank-financed road project in Uganda, the World Bank took several measures to address this issue.

In 2020, the World Bank introduced a mechanism that can disqualify contractors for failing to comply with obligations related to the prevention of gender-based violence. The World Bank will also soon launch their World Bank Gender Strategy 2024 – 2030: Accelerate Gender Equality for a Sustainable, Resilient and Inclusive Future, which recognizes gender equality as central to sustainable development. The strategy emphasizes gender outcomes in project implementation, including eradication of gender-based violence.

All PDBs should ensure that such measures (policies and practice) are put in place to avoid the ongoing violations against women that put young girls such as Lineo at high risk.

There is a growing dialogue among PDBs and United Nations Agencies such as UN Women, including those engaging in the Finance in Common movement, on the importance of financial inclusion, which places emphasis on improving women’s access to finance. PDBs must take stronger leadership in ensuring that financial inclusion addresses social issues that are an obstacle to women’s advancement. This includes removing outdated cultural practices and stereotypes that continue to create barriers to land ownership. Women in as much as half the countries of the world are unable to assert equal land and property rights despite legal protections.

PDBs often provide substantial funds to mega-infrastructure projects such as the LHWP II in which communities are often exposed to high levels of vulnerability, including worsening levels of poverty, inequality and GBV. One way that PDBs can contribute to making real progress on the Agenda 2030, is through addressing the root causes of poverty and inequality and integrating SDG 5, “achieving gender equality” a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world. There has been progress over the last decades, but the world is not on track to achieve gender equality by 2030.

In doing so, PDBs (national, regional and international) must have robust gender policies and practice in place that support projects centred on gender equality, justice and women’s empowerment.

All PDB funded projects should have gender equality imperatives at the onset of the project cycle through rigorous impact assessment processes that involve women and their communities.

The human rights costs are high in second phase of the LHWP with hundreds of families at risk of involuntarily resettlement and displacement from their homes and lands. Achieving the SDGs will require transformative action that can deliver real impact and change for women and young girls such as in Lesotho. The DBSA, AfDB, NDB and other PDBs involved in LHWP II can play an important role in ensuring that the second phase does not repeat the same mistakes made in LHWP I and in so many other development projects.

This article has been written as part of the Forus March With Us campaign for gender justice – a full month dedicated to the stories of activists and civil society organisations at the forefront of gender equality and justice.

Marianne Buenaventura Goldman is co-Chair, Civil Society Forum of the NDB (Africa) & Project Coordinator for Financing for Sustainable Development, Forus

Reitumetse Nkoti Mabula is Executive Director, Seinoli Legal Centre

IPS UN Bureau