LHDA sued

The Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA) has been sued for withholding vital socioeconomic data pertaining to communities impacted by the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) Phase I and II.

Seinoli Trust, an NGO and public interest law center recently lodged the application, representing communities affected by both phases of the bi-national project.

The Trust alleges that LHDA’s denial of this crucial information violates its own policy and legal obligations regarding access to information.

Reitumetse Nkoti Mabula, the Executive Director of Seinoli Legal Centre, explained in an affidavit that Seinoli’s request for socioeconomic data was met with refusal by LHDA.

Mabula said that the denial not only contravenes LHDA’s policy but also its legal commitments regarding access to information.

Papers filed in court reveal that Seinoli wrote to the LHDA in March and April this year requesting for the same information.

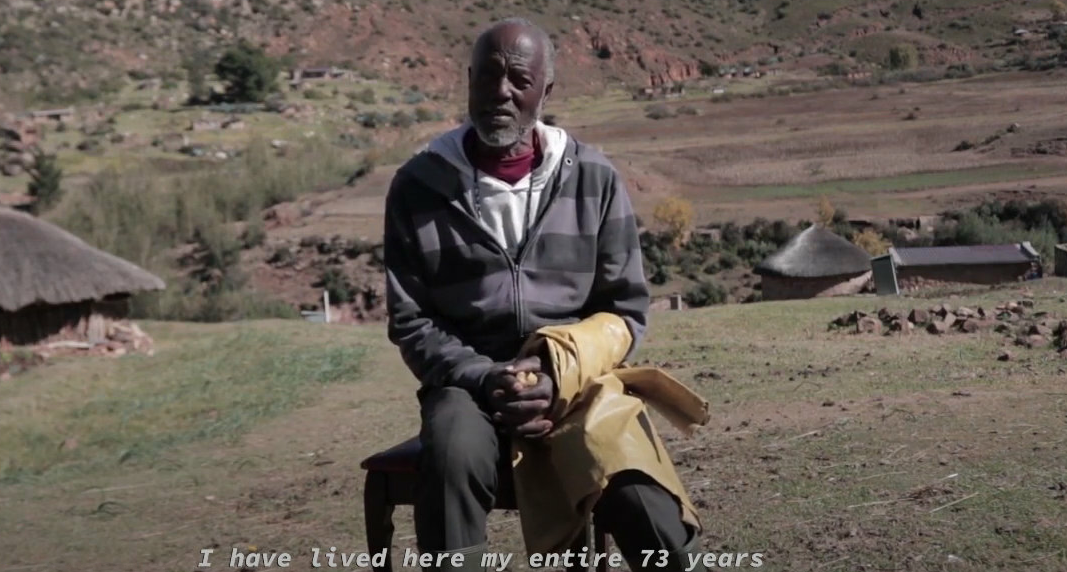

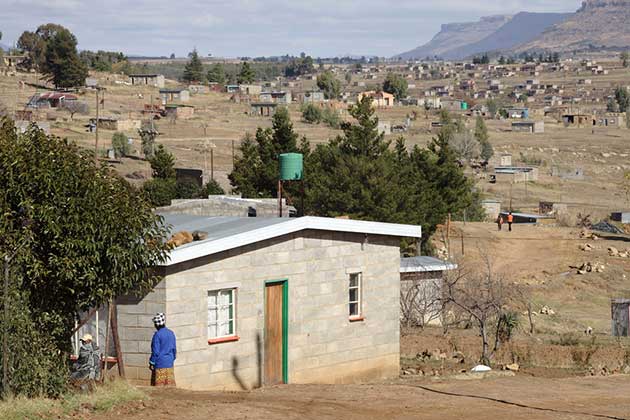

“Seinoli is deeply concerned about the dire situation derived from implementing Phase IA, of villages in the Katse catchment area. We have received many complaints relating to the implementation of the compensation policy as well as severe impact on the standards of livelihood of communities, read the letter Seinoli wrote to LHDA.

It added: “Seinoli has received witness statements from affected people describing how their livelihoods have been affected and how those changes impact human rights. To make a comprehensive assessment and conduct an in-depth analysis of the implementation of Phase IA, we request a completed census and socio-economic survey data set of all project-affected persons.

Among others, Seinoli demanded land and asset inventory, disclosure forms with valuation amounts, compensation values per asset, compensation offers, and signed agreement documents or grievance documents as well as an overview of cash compensation in kind that was paid out to affected persons.

The letter continued: To make a comprehensive assessment of the subject matter, we request the information above as we are alarmed by the available evidence, which suggests that LHDA is not acting in compliance with domestic and international law.

We are deeply concerned about potential human rights violations protected under the law of Lesotho and international agreements that Lesotho has signed and ratified.

On June 22, 2023, LHDA responded, stating that they conduct periodic studies on the socio-economic status of affected communities.

It explained that the latest study was ongoing and that the resulting information becomes LHDA’s intellectual property, making it unavailable for third-party sharing.

Based on the above, LHDA is unable to share data and information relating to the socio-economic status of the communities that have been affected by the LHWP to Seinoli Legal Centre and or any other third party, read the LHDA letter.

Seinoli Trust has now approached the High Court of Lesotho, seeking a declaration that LHDA’s refusal to provide information is unlawful. They further request a review of LHDA’s decision and its correction.

In doing so (refusing with the information), the LHDA denied the applicant (Seinoli) access to the requested critical information, thereby disabling the applicant to interrogate the critical questions on the basis of the scientific information and data in the possession of the LHDA, Mabula stated in her founding affidavit.

She argued that in terms of Clause 4.5 of the LHDA 2016 Environmental Policy, the LHDA made commitments with respect to stakeholders engagement that “LHDA will respond promptly to concerns and requests for information and will fully investigate substantive complaints.

“Section 14 of the constitution of Lesotho 1993 protects the applicants’ right to freedom of expression which includes the applicant’s right to receive information and ideas without interference.

I aver that there is no law in Lesotho that justifies the LHDA to limit applicants’ aforesaid entrenched right to access information for the purposes specified under section 14 (2) of the constitution of Lesotho 1993.

The refusal by LHDA therefore constitutes illegal interference with applicants’ constitutionally entrenched rights, she said.

She indicated that they depend on the technical, scientific or other information or data relevant to the objects of the applicant aforesaid. Consequently, the applicant is the bearer of the rights such as the right of access to information.

The state, parastatals or local authorities have the correlative duty and obligations to provide the information required by the applicant for the purpose of enabling the applicant to not only enjoy the vested rights but also to use this information as the vehicle towards achieving its objectives.

Communities affected by LHWP fall within beneficiaries of Seinoli Trust because they are vulnerable to rights violation and as such qualify for provision of free legal assistance and representation offered by the applicant, she said.

LHDA has always held that communal rights including communal resources and assets, will be identified and inventoried and will be paid communal compensation to the affected communities, she said.