Water from Lesotho for Export not villages

The Kingdom of Lesotho is one of the poorest countries in the world. In order to get more money into the state coffers, the government exports water to neighboring South Africa. Lesotho’s ecosystems and local village communities suffer as a result.

Cool spring water flows from two metal pipes that protrude from a concrete block. A shepherd is watering his sheep here, two girls are filling buckets and canisters with water. It comes directly from the mountains that surround the village of Ha Lejone in the Lesotho highlands. Transporting it is arduous: the girls bring it home in wheelbarrows and balancing it on their heads.

Access to clean drinking water is limited, as in many areas of Lesotho. But here it stands in stark contrast to the masses of water in the valley. Right next door, the huge Katse Dam glistens in the sun – the heart of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. It consists of dams, tunnel systems, pumping stations and power plants. The water is not intended for Lesotho, but for export to South Africa.The supply of food to her village has not improved, says Mammpole Molapo. On the contrary:”Before this project, we had an abundance of water here. But the road and dam construction work damaged many of the pipes that used to bring water to our village. There were promises that they would be repaired, but that has not happened in all these years. And so our village is short of water.”Molapo is the traditional village leader in Ha Lejone, a female chief. Her home village is located at an altitude of around 2,300 meters on the northern shore of the Katse Dam.

The villages have not benefited from water exports

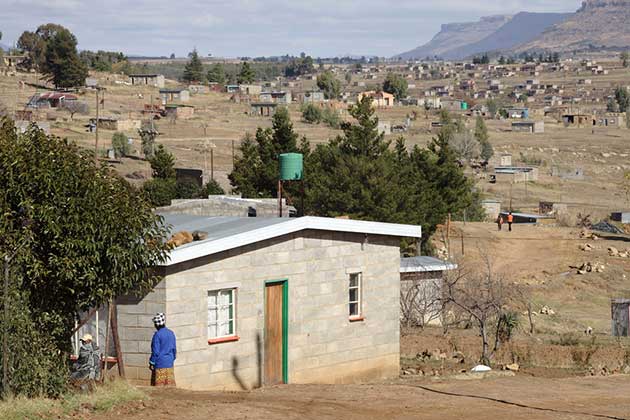

Here, small shops line the streets and men load sheep onto a pickup truck. Some houses are traditionally built from natural stone, covered in grass and round. Modern, rectangular houses with corrugated iron roofs can also be seen in the landscape.

.

Leonie March in conversation with the village head of Ha Lejone: Mammpole Molapo. In the background is NGO employee Mothusi Seqhee.© Roger Jardine

Ha Lejone used to be difficult to reach via unpaved mountain passes. Since the tarmac road was built in the 1990s as part of the dam project, it has become easier to travel to the lowlands. The road construction is being touted by Lesotho’s government as an advantage, as are hydroelectric power and water charges, which brought around 58 million euros into the small kingdom’s coffers last year alone. Part of this should go towards the development of villages like Ha Lejone.But that is not the case, says village mayor Molapo. The bottom line is that her life has not improved. The small-scale farming life of her childhood no longer exists.”We used to have a decent life. We were subsistence farmers and grew enough to feed our families. But many fields and pastures have been flooded for the project. Natural resources that we used are now under water too. For example, medicinal plants. They are now only available in a botanical garden, but that is at the other end of the reservoir. It is a long, expensive journey for us. We also have to pay for the medicinal plants there.”Molapo looks out over the steep, rocky mountain slopes. Shepherds drive their cattle across the landscape on foot and on horseback: cows, sheep, Angora goats. There are no fenced pastures. The land is traditionally used by everyone. Since the valley was flooded, only the slopes remain.

Dams change ecosystems

In many places they appear to be terraced and erosion is increasing. This is also fatal for the water supply: wetlands, which play an important role in the alpine ecosystem, storing and filtering water, are increasingly under pressure, says ecologist Peter Chatanga.”Some of the roads lead through such wetlands. This changes their hydrology, for example they become more easily silted and can no longer fulfil their function as water reservoirs. The dams also change the ecosystem and reduce the pastureland, which in turn leads to overgrazing. Since these areas in the highlands have become more accessible, the population has also increased. This also increases the man-made pressure on the wetlands.”

The Katse Dam near Ha Lejone filled the valley with water.© Roger JardineAdd to that climate change: in the face of a drought, Lesotho had to reduce water exports to South Africa in 2020 for the first time in ten years. And this trend could continue. More droughts, more floods, a less predictable rainy season.Climate change will manifest itself in more extremes in Lesotho, says Henrik Hartmann of the German Society for International Cooperation, GIZ, in Lesotho. However, a study also shows that climate change is not the only reason for the steadily falling water levels in reservoirs over the past 20 years.”There is strong evidence that it is due to the destruction of ecosystems. And this study that we have carried out also shows the consequences that would have. If you assume that the water transfer to Johannesburg could be interrupted by 50 percent, that would have enormous effects on the metropolis itself. You can assume that there will be a ten or eleven percent economic contraction. You can assume that a million jobs will be lost. You can also assume that in Lesotho itself, due to the loss of income, enormous savings will have to be made – in the areas of health and education. In that respect, this is a relevant problem, not just ecologically, but also economically and socially.”

50 to 60 percent of people live in absolute poverty

The income from water exports accounts for a significant portion of the national budget in Lesotho. The country is one of the poorest in the world. If income falls, the resources for poverty reduction also shrink. However, this is crucial for protecting ecosystems, explains Henrik Hartmann of GIZ.”The root cause of ecosystem damage in Lesotho is poverty. It is because people have no other sources of income than subsistence farming. We see this in some of the areas where we work: According to the official definition of absolute poverty – US$1.90 – 50 to 60 percent of people are below that. This means that we are dealing with people who are chronically food insecure. And you cannot approach this with a protection approach where you say: it is now only about protecting the ecosystems.”Therefore, it is not just about establishing new protected areas, but about using natural resources more sustainably. These can be simple solutions, such as growing new crops that require less water than maize, which has dominated until now. Or building drinking troughs on the edge of wetlands. This allows herders to water their livestock without entering the sensitive ecosystems. Environmental protection, poverty reduction and economic development must go hand in hand.Villages like Ha Lejone on the edge of the large dams had also hoped for a better life, a way out of poverty. The responsible government agency, the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority, had promised tourism projects and the establishment of fishing businesses, among other things. But the results are sobering.

Villagers’ legal battle against the government

The village committee of Ha Lejone has gathered in a small room to discuss what to do next. Men and women sit on wooden benches wrapped in blankets and listen to the news that Mothusi Seqhee brings from the capital, Maseru. He works for the Seinoli Legal Centre – a non-governmental organization of lawyers that represents the interests of the rural population and reports on the long struggle of the villagers.”The contract was signed by Lesotho and South Africa in October 1986, and construction work on the dam began about three years later. The people here and in the other affected areas were promised a better life and compensation. For example, for the loss of pastureland. At first they received animal feed, regardless of whether they had livestock or not. After that there was financial compensation, but only until 2004. Then no money was paid for years, even though annual payments had been agreed. So we went to court and won in 2015.”But the fight is not over yet. The Lesotho Highlands Development Authority said it had stopped payments due to cases of mismanagement in the communities. Now the villagers are obliged to set up committees, document their expenses precisely, have them approved by auditors and even submit business plans.”The intention may have been good, but the implementation is a problem. The responsible authority did not support the committees as intended, for example in drawing up business plans. The people here did their best. They proposed various projects, including a trout farm for the local market. But all their ideas were rejected – and without giving any concrete reasons. In other words: the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority is not interested in the development of these communities. At the same time, it is keeping money that does not belong to it.”NGO employee Mothusi Seqhee alludes to both the lack of compensation payments and the corruption scandals of recent years: funds were embezzled, bribes were paid, and even prison sentences were imposed. Corruption is also considered to be the reason why the completion of the second phase of the bilateral project between Lesotho and South Africa has been delayed by years. In this case, the South African side is under suspicion. Instead of 2019, more water will now only flow to South Africa in 2026. For Lesotho, this means that revenues will not increase. And for South Africa, it means that water is becoming scarce in the Gauteng economic region around Johannesburg, where twelve million people live.

Construction work for another dam

Clean drinking water is already rare in Masakong. The small village is located on a bend in the river, where another dam is to be built as part of the second phase of the project. Heavy construction machines drive over the new tarred road, dust blows over the former pastureland and fallow fields of small farmers. A fence has been built around their village, and the path to the river is also blocked. Residents like Lebohang Lengoasa have been waiting for years to be relocated.”We lead a miserable life. We are literally surrounded here and have lost our livelihood: our fields and our livestock. My animals died in the last drought, others ate plastic waste that was not here before. But we are still waiting for the promised compensation, jobs and relocation of our village.”Lengoasa takes a few steps towards a water tap that protrudes from the ground between his fenced-in village and the large construction site. The villagers used to get their drinking water from a spring, but it was contaminated by wastewater from the construction workers’ settlement. The project management therefore installed this communal water tap.”They first pump the water from the river into the plastic tanks over there. They say they filter it before it comes out of the tap here. But we have doubts about that: when it rains, the water is brown, it smells and tastes strange. Some of us boil it because of that, but not all of us. Children regularly get diarrhea. But when I denounce these abuses, they try to intimidate me.”What will happen next? Lengoasa shrugs his shoulders helplessly. Some of his neighbors have already moved to the city, others are holding on to the hope of somehow building a new life for themselves here in the highlands.

Renegotiate water project?

The government of Lesotho is trampling on the rights of its own citizens, says NGO worker Mothusi Seqhee. The original contract for the cross-border water project was signed in the 1980s, when apartheid was still in place in South Africa and a military regime in Lesotho. He would have expected more from today’s democratically elected governments.”They have the same mentality and approach to the affected citizens as before. Our politicians are not thinking about how the project could actually benefit our country. We should at least be allowed to use the water from the dams for irrigation so that we can produce enough food for the nation. The government should appoint experts to develop viable and sustainable projects to provide new livelihoods and replace the land that the people here have lost.”And of course every citizen has a right to clean drinking water. But the authorities are stubborn, says Mothusi Seqhee, who will soon be going back to court with his NGO’s lawyers.

This research was funded by the European Journalism Centre as part of the Riffreporter project ” Countdown Nature “.